Introduction

In this post, we will answer the following 5 questions:

- Why do we need a software architecture?

- What is a Monolithic Architecture?

- What is a Layered Architecture?

- What is a Microservices Architecture?

- Other Architectures

If you are a self-taught developer, new to the industry, or something of the sort, the concept of "software architecture" is intimidating. Enterprise architects get paid lots of money because architecting a quality software is difficult and requires experience.

You may have the following concerns:

- How am I supposed to architect a solution with little prior experience?

- There are so many architectures and design patterns. What if I choose the wrong one?

- How can I create an entire architecture without knowing all the details about the code I'm going to write?

Throughout this post, we'll work through these concerns and figure out what this architecture thing is all about.

Why do we need Software Architecture?

"Any intelligent fool can make things bigger, more complex, and more violent. It takes a touch of genius—and a lot of courage to move in the opposite direction"

From E.F. Schumacher's book Small is Beautiful, this quote embodies a lot of what architecting software means. As a developer, it is always more fun to solve a complex problem in a complex way. It's more fun to create a Rube Goldberg Machine than walking from point A to point B and dropping the marble in the cup.

Unfortunately, as a developer and architect, you get no additional bonus points for indirectly solving problems. You make the real money by solving a complex problem in a simple way.

Designing software architecture is about arranging components of a system to best fit the desired quality attributes of the system.

- The user cares that your system is fast, reliable, and available

- The project manager cares that the system is delivered on time and on budget

- The CEO cares that the system contributes incremental value to his/her company

- The head of security cares that the system is protected from malicious attacks

- The application support team cares that the system is easy to understand and debug

There is no way to please everyone without sacrificing the quality of the system. Therefore, when designing software architecture, you must decide which quality attributes matter most for the given business problem. Below are a few examples of quality attributes:

- Performance - how long do you have to wait before that spinning "loading" icon goes away?

- Availability - what percentage of the time is the system running?

- Usability - can the users easily figure out the interface of the system?

- Modifiability - if the developers want to add a feature to the system, is it easy to do?

- Interoperability - does the system play nicely with other systems?

- Security - does the system have a secure fortress around it?

- Portability - can the system run on many different platforms (i.e. Windows vs. Mac vs. Linux)?

- Scalability - if you grow your userbase rapidly, can the system easily scale to meet the new traffic?

- Deployability - is it easy to put a new feature in production?

- Safety - if the software controls physical things, is it a hazard to real people?

Depending on what software you are building or improving, certain attributes may be more critical to success. If you are a financial services company, the most important quality attribute for your system would probably be security (a breach of security could cause your clients to lose millions of dollars) followed by availability (your clients need to always have access to their assets). If you are a gaming or video streaming company (i.e. Netflix), your first quality attribute is going to be performance because if your games/movies freeze up all the time, nobody will play/watch them.

As you can see, the process of building software architecture is not about finding the best tools and the latest technologies. It's about delivering a system that works effectively. But why do we need an architecture to do this?

According to the book Software Architecture in Practice, there are 13 reasons why Software Architecture is important for the success of a project. Of those 13, I pulled out a few that might resonate with a smaller team or individual developer:

- Architecture enables quality attributes - For example, a peer to peer architecture is naturally going to have high availability due to the decentralized nature of the system. A microservices architecture will have high modifiability due to the segregation of duties.

- Architecture enables communication among stakeholders - When the architecture closely resembles the structure of your company, everyone knows which part of the software they are responsible for.

- Architecture focuses on the assembly rather than creation of components - Rather than focusing on how the code is written, architecture forces us to think about how the components in the system talk to one another.

- Architecture restricts design choices, enabling creativity in other areas - By defining some boundaries in your software project, you know which areas you can get creative in without hurting the progress or quality of the system.

The book points out that design decisions made at the beginning of a project have a disproportionate weighting and restrict the ability to change certain areas of the software later on, so it is important to spend time to understand the requirements of the software and design it to the best of your ability from the start.

This is where an experienced architect has an advantage over a novice. They can see much further into the future and anticipate how certain design decisions will impact the system.

For those of us (including myself) not so experienced in designing architecture, we must accept that things won't be perfect and design it anyway. Yes, revisions will have to be made, but what other choice is there?

There are many architectures to choose from, but not all of them are "beginner friendly" and sometimes require years of experience to implement correctly. For example, creating an effective peer-to-peer architecture (i.e. Bitcoin, Bittorrent) is no easy undertaking.

To keep things simple, I will be walking through 3 common architectures that cover a wide variety of use cases. Unless you have a specific reason and design experience to justify going a different route, one of these three architectures will usually suffice no matter what technology stack you use.

I chose these three because they seem to come up the most often in software communities. There are other useful architectures like Event-Driven, Client-Server, Microkernel, and more, but if you do not understand the 3 below, it would not make sense to attempt any of these advanced architectures anyways.

Update (10/24/20): Thank you, Carlos G for pointing this out in the comments--When talking about these 3 architectures, they are not perfect comparisons. A monolithic and microservices architecture talks about how an application is distributed while a layered architecture refers more generally to how one might design the internal components of say a monolithic app or single microservice. In other words, just because it is a monolith does not mean it has a poor "layered" design. Likewise, just because you have a microservices architecture in place does not ensure that you have a perfectly "layered" codebase within it. In summary, the "monolithic" architecture example below is not so much architecture, but an example of poorly written code that doesn't have a separation of duties (aka "layered"). Furthermore, the "layered" example below would more accurately be classified as a "properly written monolith".

I believe the easiest way to learn software architecture is to see it in practice. You have certainly seen different architectures while reading through codebases, but you probably haven't recognized them. My examples below are not meant to demonstrate the proper way to code an application, but rather to explicitly call out the various architectures that you can use within your codebase. To demonstrate, I will be using NodeJS, ExpressJS, and MongoDB in the context of a web application.

Monolithic Architecture (with poor "layered" design)

All code mentioned below is stored in my monolithic architecture repository on Github

If you have ever taken tutorials online that teach you how to build a web application, you have most likely built a monolithic application. It is by far the easiest to conceptualize starting out.

A monolithic architecture describes an architecture where all of the following components are bunched into one codebase:

- Views (i.e. HTML, CSS, Javascript)

- Application/Business Logic (i.e. ExpressJS)

- Data Access/Database (i.e. MongoDB)

Although this architecture may seem ineffective, not all industry professionals believe it is useless. For example, Martin Fowler advocates for the use of monolithic architectures when starting a new application. He notes that those who start their applications as microservice architectures usually end up wasting time and energy because you don't start seeing the benefits of this architecture until the application becomes complex.

He suggests starting with a monolithic architecture and refactoring it later into a layered or microservice architecture when it becomes too large to handle all in one piece.

Let's take a look at the internals of a simple monolithic architecture.

Application Structure

All code mentioned below is stored in my monolithic architecture repository on Github

The main thing that you will see with this code is a lack of distinction between application parts. For example, in app.js, you will see a connection to the database, the server, and even some API endpoints.

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

const mongoose = require("mongoose");

const cors = require("cors");

const bodyParser = require("body-parser");

// This will allow our presentation layer to retrieve data from this API without

// running into cross-origin issues (CORS)

app.use(cors());

app.use(bodyParser.json());

// ============================================

// ========== DATABASE CONNECTION ===========

// ============================================

// Connect to running database

mongoose.connect(

`mongodb://${process.env.DB_USER}:${process.env.DB_PW}@127.0.0.1:27017/monolithic_app_db`,

{

useNewUrlParser: true,

}

);

// User schema for mongodb

const UserSchema = mongoose.Schema(

{

name: { type: String },

email: { type: String },

},

{ collection: "users" }

);

// Define the mongoose model for use below in method

const User = mongoose.model("User", UserSchema);

function getUserByEmail(email, callback) {

try {

User.findOne({ email: email }, callback);

} catch (err) {

callback(err);

}

}

// set the view engine to ejs

app.set("view engine", "ejs");

// index page

app.get("/", function (req, res) {

res.render("home");

});

// ============================================

// ============ API ENDPOINT ================

// ============================================

app.post("/register", function (req, res) {

const newUser = new User({

name: req.body.name,

email: req.body.email,

});

newUser.save((err, user) => {

res.status(200).json(user);

});

});

// ============================================

// ============== SERVER =====================

// ============================================

app.listen(8080);

console.log("Visit app at http://localhost:8080");

If we wanted to add another API endpoint, we would need to edit app.js. If we wanted to add another database Model, we would need to edit app.js. Even if we wanted to modify an API call in home.ejs, we would probably need to make changes to app.js.

This centralization we see is not sustainable into the future, but that doesn't mean it is all bad. As mentioned above, you may find it useful to start out with something like this and as the application grows, start refactoring the pieces into a more manageable architecture. One of the ways we can refactor is through the concept of a layered architecture.

Monolithic Architecture (with better "layered" or "n-tier" design)

After a while, your monolithic application will start getting big, you will start hiring people, and it will quickly become a mess. Although many modern architects will turn to a microservices design to solve this problem (covered in the next section), another option to better segregate the duties of the application is to refactor your monolith.

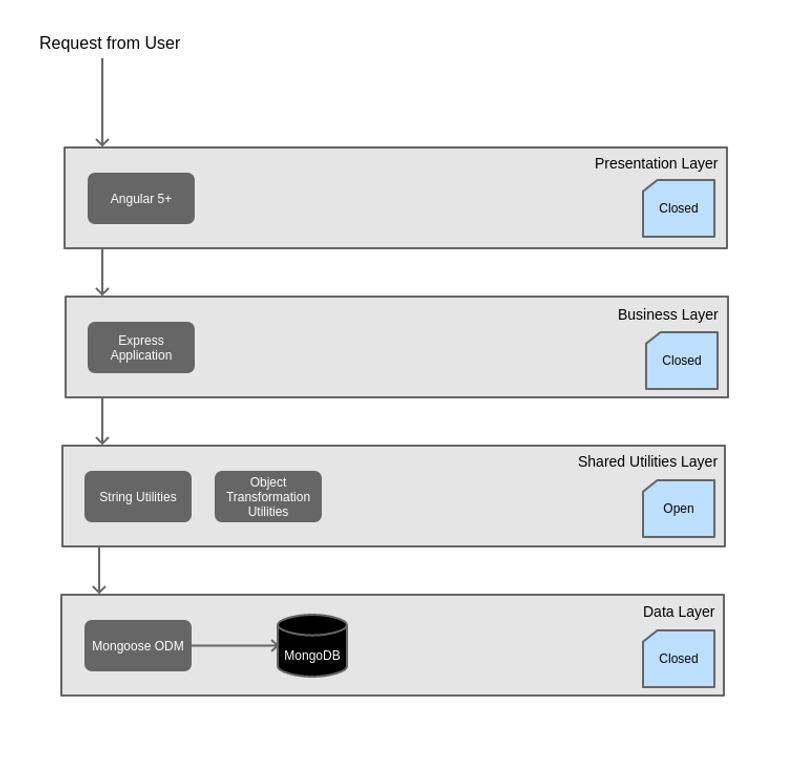

The layered architecture splits your application into layers. Usually, you will find the following layers (in order):

- Presentation Layer

- Business Layer

- Data Access Layer

You may also stumble upon alternate terminology:

- Presentation Layer

- Application Layer

- Domain Layer

- Persistence Layer

No matter what you call the layers, the point is to create a "separation of concerns" where each layer is only allowed to use the layer directly below it.

In some cases, you may have a shared layer that has utility functions. In this case, you could create an additional layer that is considered "open" for all layers to use. Other layers are considered "closed" which means they can only use the layer below them.

Application Structure

All code mentioned below is stored in my layered architecture repository on Github

The critical factor in a layered architecture is the rule that each layer can only utilize the layer directly below it. In the sample app linked above, I have created a basic User Authentication flow that illustrates this concept. Furthermore, code from each layer is stored in a clearly marked folder (i.e. business-layer).

In our example, the flow has the following steps:

- Presentation layer makes a call from an HTML user form

- Presentation layer javascript processes the form and executes a call to the business layer

- Business layer processes the form info and makes a call to the data access layer

- Data access layer processes the information and makes a query to the database for the user

- Data access layer returns the information to the business layer

- Business layer returns the information via HTTP to the presentation layer

- Presentation layer renders the view with the new information

Let's walk through the steps with code now.

1. Presentation layer makes a call from an HTML user form

<!-- File: home.ejs -->

<!-- On form submit, home.ejs executes the getDataFromBusinessLayer() function -->

<form id="emailform" onsubmit="getDataFromBusinessLayer()">

<input name="email" id="email" placeholder="Enter email..." />

<button type="submit">Load Profile</button>

</form>

2. Presentation layer javascript processes the form and executes a call to the business layer

// File: presentation-layer-user.js

function getDataFromBusinessLayer() {

event.preventDefault();

const email = $("#email").val();

// Perform the GET request to the business layer

// ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

$.ajax({

url: `http://localhost:8081/get-user/${email}`,

type: "GET",

success: function (user) {

// Render the user object on the page

// Ommitted for brevity

},

error: function (jqXHR, textStatus, ex) {

console.log(textStatus + "," + ex + "," + jqXHR.responseText);

},

});

}

3. Business layer processes the form info and makes a call to the data access layer

// File: business-layer-user.js

app.get("/get-user/:useremail", function (req, res) {

// Makes a call to the data access layer

// ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

const user = User.getUserByEmail(req.params.useremail, (error, user) => {

res.status(200).json({

name: user.name,

email: user.email,

profileUrl: user.profileUrl,

});

});

});

4. Data access layer processes the information and makes a query to the database for the user

// File: data-layer-user.js

module.exports.getUserByEmail = (email, callback) => {

try {

// Makes a call to the database

// ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

User.findOne({ email: email }, callback);

} catch (err) {

callback(err);

}

};

5. Data access layer returns the information to the business layer

No relevant code to show

6. Business layer returns the information via HTTP to the presentation layer

No relevant code to show

7. Presentation layer renders the view with the new information

No relevant code to show

As we walked through each of the steps, you may have noticed how each layer is responsible for a very specific duty. This requires more thought and time to implement but allows for greater organization as the project grows. This also allows multiple team members to work on the application at once. You could have one team implementing all of the database calls in the data layer, another team implementing the REST API in the business layer, and another team creating the front-end user interface!

This sounds great, but there is one problem that this architecture does not solve. The layered architecture still operates as a single application. If you want to make any large changes to a single layer, you will have to re-deploy the entire application to implement the changes. In other words, you will always have a daily/weekly/monthly "release schedule" where the entire application goes down for a brief moment and the new changes are released to the public.

Microservices Architecture

All code mentioned below is stored in my microservices architecture repository on Github

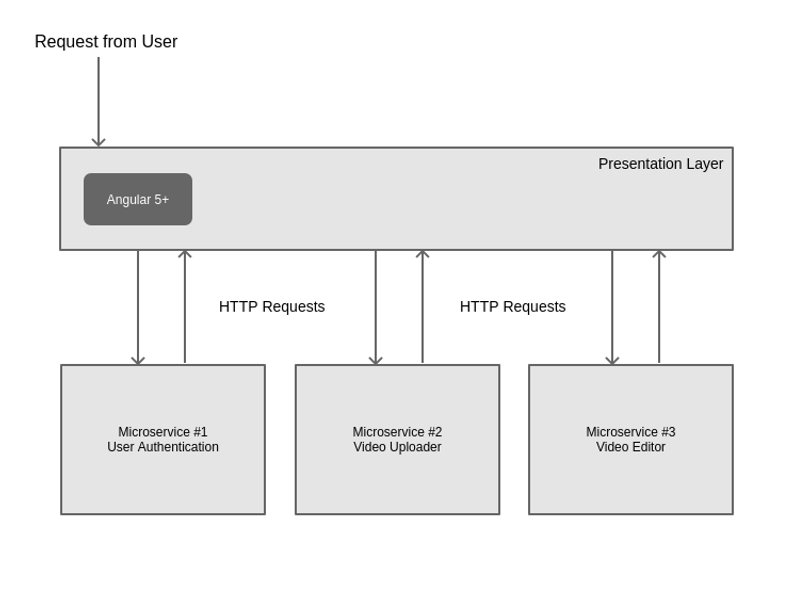

A layered, monolithic architecture is suitable for many applications, but one of the trends in software as of late is a migration towards microservice architectures. It solves the "release schedule" problem and allows developers to independently engineer each piece of a larger application.

If each piece of your architecture is self-sufficient and does not require anything from other pieces of the application, you have a microservices architecture.

Application Structure

In the code mentioned above, we have three parts to our microservices architecture:

- View Server (localhost:8080) - This server runs all of the front-end application logic which includes the main

index.htmlfile that utilizes multiple microservices. - User Authentication Server (localhost:8081) - This server manages all user authentication.

- Game Server (localhost:8082) - This server controls the game that is played on the screen.

Notice how each of the servers run independently on different ports. This means you could host them on completely different servers and still make the application work. Each piece of the application communicates through HTTP protocol and therefore can operate independently.

One thing that you might notice if you look at the code linked above is the presence of a layered architecture within each microservice. This is where architecture gets a little fuzzy. You can have a microservices architecture that utilizes a layered architecture within each microservice. Although there are no strict rules on how you must build your microservices, it is common to utilize something like a layered architecture to structure them.

As we walk through the pieces of this application, notice how we are not talking about "call chains" anymore. Instead, we are talking about API endpoints (i.e. the communication between the microservices).

Microservice #1 - User Authentication (http://localhost:8081)

Note: The password authentication is not implemented as you should in a production application; it is solely for demonstration and you should never store your users' passwords in plain text like I am doing here!

This microservice is solely responsible for creating and authenticating users.

In many complex applications, an entire server will be devoted to authenticating and managing users. After all, without users, you have no application. Therefore, it is critical to not only implement the user functionality but maintain proper security and protect the users' data.

To understand why a user authentication microservice might be useful, imagine a large company that offers a wide variety of services to its users. A perfect example is Google because you not only use your login credentials for Gmail and other core Google services; you also use it to log into YouTube and many other applications.

Imagine if Google implemented a user authentication scheme in each individual application!! This is highly inefficient, so instead, Google created a "microservice" that functions like user authentication for not only Google applications, but an increasingly large number of 3rd party applications. This is made possible because the authentication microservice is decoupled from the underlying infrastructure with robust APIs. This is the goal of microservices.

You will see in the application that I have created a much much much much much (did I say much?) simpler authentication microservice than what Google owns. Nevertheless, it demonstrates how we might implement an "authentication API" for one or more applications.

Below, you'll see the three API endpoints that this microservice exposes:

app.post("/register", function (req, res, next) {

const newUser = new User({

email: req.body.email,

password: req.body.password,

});

User.createUser(newUser, (err, user) => {

res.status(200).json(user);

});

});

app.post("/authenticate", (req, res, next) => {

const email = req.body.email;

const password = req.body.password;

User.getUserByEmail(email, (error, user) => {

if (user && user.password == password) {

// User entered the correct password and we should authenticate them!

res.status(200).json({ authenticated: true });

} else {

// User entered the wrong password

res.status(200).json({ authenticated: false });

}

});

});

app.get("/get-user/:useremail", function (req, res) {

User.getUserByEmail(req.params.useremail, (error, user) => {

res.status(200).json({ email: user.email, password: user.password });

});

});

Our front-end user application can use these three endpoints at localhost:8081 to manage users!

Microservice #2 - Game (http://localhost:8082)

This microservice is solely responsible for managing gameplay results of all the application users registered through the authentication microservice.

The game microservice is a bit simpler than the user authentication microservice but demonstrates how we can separate core pieces of functionality of our applications. Although this is a simple game, you could imagine a much more complex scenario where the game had all sorts of graphic elements and user data.

Below are the two API endpoints that the Game microservice exposes:

// Register API Call

app.post("/score", function (req, res, next) {

const score = req.body.result;

const winValue = score == "win" ? 1 : 0;

const lossValue = score == "loss" ? 1 : 0;

const email = req.body.email;

// See if user has posted a score already

Game.getUserScoresByEmail(email, (err, user) => {

// If user hasn't posted a score yet, create an entry for their count in the database

if (!user) {

Game.createUserWithScore(

new Game({

email: email,

wins: winValue,

losses: lossValue,

}),

(err, user) => {

res.status(200).json(user);

}

);

} else {

// If user already has posted a score, update his/her win and loss count based on result

Game.updateUserScores(email, winValue, lossValue, (err, count) => {

res.status(200).json(count);

});

}

});

});

app.get("/score/:email", function (req, res, next) {

Game.getUserScoresByEmail(req.params.email, (err, user) => {

res.status(200).json(user);

});

});

The user interface will make calls to localhost:8082 to update a user's gameplay stats.

Bringing it all together: The User Interface

We have walked through the API endpoints that each microservice exposes, but these endpoints are useless without a user interface to help the user interact with them!

In this user interface, index.html has a bunch of click listeners that will execute API calls when certain events happen. For example, when a user enters information into the register form and clicks the register button, the following function is triggered, and a POST request is sent to the /register endpoint.

function register() {

const email = $("#register-email").val();

const pw = $("#register-pw").val();

event.preventDefault();

$.ajax({

type: "POST",

url: "http://localhost:8081/register",

data: JSON.stringify({ email: email, password: pw }),

contentType: "application/json; charset=utf-8",

dataType: "json",

success: function (result) {

setTimeout(() => {

$("#register-message").toggleClass("hide");

}, 3000);

$("#register-message").toggleClass("hide");

},

});

}

You can see that the url property is set to our User Authentication microservice.

There is another click listener on the buttons that start and stop the game. When the game is stopped, the following function is triggered, and a POST request is sent to the /score endpoint:

function stopSpinner(position) {

let coordinatesArray = position.slice(7).split(",");

let c1 = Math.abs(parseFloat(coordinatesArray[0]));

let c2 = Math.abs(parseFloat(coordinatesArray[1]));

let result;

let email = localStorage.getItem("email");

if (!email) {

setTimeout(() => {

$("#logged-out-warning").toggleClass("hide");

}, 3000);

$("#logged-out-warning").toggleClass("hide");

}

if (c1 >= 0.9935 && c1 <= 1 && c2 >= 0 && c2 <= 0.12) {

result = "win";

setTimeout(() => {

$("#winner").toggleClass("hide");

}, 3000);

$("#winner").toggleClass("hide");

} else {

result = "loss";

setTimeout(() => {

$("#loser").toggleClass("hide");

}, 3000);

$("#loser").toggleClass("hide");

}

if (email) {

$.ajax({

type: "POST",

url: "http://localhost:8082/score",

data: JSON.stringify({ email: email, result: result }),

contentType: "application/json; charset=utf-8",

dataType: "json",

success: function (result) {

console.log(result);

},

});

}

}

Finally, when you click the button to see your scores, the following function is invoked, and a GET request is sent to the /score/:email endpoint.

function seeScores() {

const email = localStorage.getItem("email");

$.ajax({

url: `http://localhost:8082/score/${email}`,

type: "GET",

success: function (user) {

$("#wins").text(user.wins);

$("#losses").text(user.losses);

},

error: function (jqXHR, textStatus, ex) {

console.log(textStatus + "," + ex + "," + jqXHR.responseText);

},

});

}

Other Architectures

Although I only talked about monolithic, layered, and microservice architectures, there are many others to choose from. As you become more experienced, you may begin to see the usefulness of other architectural patterns.

For example, if you were trying to build a platform like Wordpress that has a core system which can be extended via plugins, you might opt for a microkernel architecture. If you were trying to build Bitcoin, you might look at a peer-to-peer architecture. If you wanted to build an instant messaging system or chat application, you might look towards and Event-Driven Architecture.

One last point

Don't try to think about software architectures like I originally did--mutually exclusive. As we saw above, you can have a monolithic application with a "layered" approach within. You could even add some event-driven architecture if you wanted.

So as you think about architectures, just remember that an application (or microservice) can have several "architectures".

Conclusion

Whatever your situation, there is an architecture out there for you. Remember, the ultimate goal with architecting software solutions is twofold:

- Solve your problems in the simplest way possible

- Design your architecture to address the quality attributes you desire in your system

If you can meet these two requirements, you have succeeded. Don't fall into the architecture astronaut trap. Don't fall into analysis paralysis. Build something that works and call it a day.